Below, in an extract from it, she describes with searing honesty her reaction to being told her life would be cut drastically short - and how to act around the dying.

There is a raw agony that comes when the earthquake first hits.

When we were told that I had cancer, and then again when we were told it had come back, and that this time there wasn't a hope of a cure.

The agony will return when we are told I have weeks left, not months.

I can feel it threatening even as I write, with my treatment options running out.

That initial period after impact is searing.

Now, I look back on the days we've had following Bad News, and I can remember almost every instant. What I did. What I said to whom.

The words that kept going round in my head: Not Yet, Not Yet.

How the image I had in my head of death was of me in the back of a black taxi, leaving an awesome party before the end, just when everyone else was starting to have real fun.

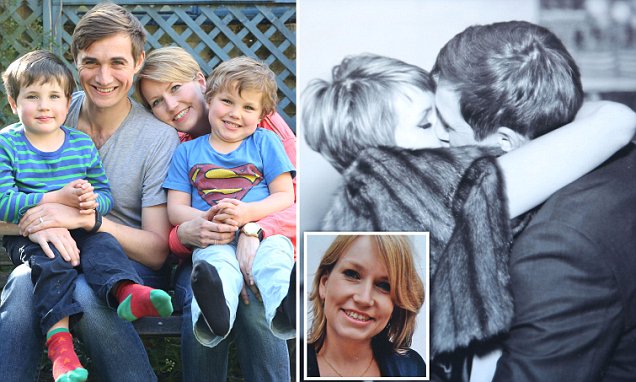

I remember my husband, Billy, crying and telling me his heart was broken.

I remember what my boys, Oscar and Isaac, said when I told them my tummy hurt was back, and I had to start having my sleepy medicine again, and how they reacted with absolute horror that we couldn't go swimming together any more.

This, truly, was the end of their little world.

When I tell you what happened next, remember that I am not unusually unfeeling, but am basically wired for happiness.

The sadness left me. Or perhaps it is fairer to say it settled in; it became part of my mental furniture rather than a monster which inhabited my mind against my will.

The sadness and I came to an accommodation with one another: if I let it out for a good wail every few days, it wouldn't assail me at inopportune moments.

The acute period of misery was short-lived - days or weeks.

I think this was because we humans cannot exist in a state of heightened emotion for long.

We are programmed to normalise, even after the worst news imaginable.

Living with the after-effects of the quake is much harder than surviving the initial impact.

There is a point when everyone else has gone back to normal life, when the spotlight isn't on you any more, and it is then that things are at their toughest.

There is a third state, between crisis and endurance: uncertainty.

Living with this is my Achilles' heel. Over the past couple of years I have explored different routes to find a way to live with this uncertainty.

Mind over matter, to begin with. Yoga. Meditation. Cognitive behavioural therapy.

It helps, it really does. But frankly all this quietude doesn't touch the sides of the gaping hole that cancer has blasted through my sense of assurance.

I have started kneeling down in forest glades and old, cold churches and asking for help.

The God I find there - the one who helps me cling on to a still, small voice of calm - is the God of churches at smokefall, a God who swims in cold seas, inhabits high mountains and wild places.

Being outside, among nature, among all of this, is the one unfailing way I have found to stop my Achilles' heel from crippling me.

I can weep on anyone, but no one gets to weep on me. (Of course you're sad that I'm dying, but I just don't need to hear you snuffle snottily that you're so devastated that I'm going to leave my children motherless. Hold it together, go cry on someone else.)

Don't assume that you should crowd towards the centre of the spiral. Leave us space to breathe.

The shoulder to cry on, the bunch of flowers, the pre-cooked dinner might be even more helpful to someone else.

My mum, who is your friend. My sister, who is your colleague.

We all want to feel we are doing something. But there is no blanket list to suit all families and all occasions, and you will have to work hard to establish a rhythm of assistance which supports but doesn't intrude.

Ask what we need, and if you are met with silence, make suggestions.

And then ask again in six months' time, because the chances are that that is the point at which everyone else will have stopped offering help.

And if you still don't get an answer? Well, maybe just do it. Managing all the help that is offered is tiring.

Sometimes I just want someone to sweep in uninvited and quietly do the ironing and not ask for any acknowledgement of the good deed they have done.

When we had the news that my cancer had returned, this time without hope of a cure, from some quarters there was silence.

I understand that. If this were happening to someone else, I would have been one of the silent bystanders, sympathetic but convinced that whatever I said would be a blundering imposition. I would have been wrong.

There is really nothing you can say that will make things worse, after all. And we don't expect great words of wisdom or solace.

You can tell me I look great, even if I don't. But please don't treat me as if I'm a dying saint who has granted you an audience in her final hours.

Don't hold our moments together in some precious reverence. Don't make me feel as if this is the last time we will meet.

The invalid craves normality, not exceptionalism. I expected support, but not solace. But solace has come, from inner circles and from outer reaches of the spiral.

After the initial silence, I have been amazed by people's ability to reach me with their words.

People open themselves up to me, revealing the pain of their own loss (mothers, fathers, friends, children), their loneliness, their fears.

What has helped them through their own earthquakes, big and small.

But don't assume that I don't want to share your joy. My whiff of envy at a new house, a cash windfall, a delightful new baby, magically disappeared when my cancer arrived.

Now I just need more good news in my life. I love to be told about an awesome new job.

I long for news of pregnancies and births. And though I spend a lot of time navigating the big things in life, I've never been more interested in trivialities.

If you are lucky, I will tell you about my trivialities too.

How I hate to look at my fat, round face in the mirror.

How consumed I am by an obsession with Crunchie bars.

How scared I am of the toad that lives in the back garden and jumps over my feet as I write in the sunshine.

I want to be communicated with but I dread the burden of reciprocation.

I know this is not the polite way we normally do things, but I figure I can break the rules now; so make it all right, and sign off with a breezy "No need to reply".

I love to be indulged with letters and cards, which can be read at leisure and treasured by my beloveds for ever.

I have boxes of letters received in the past few years.

Behind those, there are boxes of the letters from before: cards from Billy, letters written to school friends, my stash of pre-Billy Darling letters, 'stiff in their cardboard coffins', as Carol Ann Duffy put it.

Fragments of all my past lives stored up to gather dust and to remind people that once I existed.

Sometimes I sit with these boxes of letters in front of me and let the papers spill out over my feet.

All those words. Pictures. Memories. Love.

The spiral holds me tightly and squeezes my hand.

It whispers Julian of Norwich's calming mantra: All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.